This post is a response to Doug Belshaw’s post: Learning Taxonomies: Why ‘creating’ is not a cognitive skill.

While I do agree that ‘creating’ does not belong above evaluation and that there is room for some revsion of Bloom’s Taxonomy, I do believe that ‘creating’ is a cognitive skill. In fact, I believe that it should be an integral part of all learning taxonomies; that you can’t be fully literate until you have created something.

You can’t create something without some prior knowledge. It is from this knowledge that you can make decisions and by it’s very nature ‘decision making’ is a cognitive skill. Moreover, all creation is a result of our experiences. Arguably, there is no originality in creation any way (Strinati, 1997). When we create we make both conscious decisions and unconscious decisions, based on our learned experiences.

To take Doug’s son creating his first piece of art as an example: Yes he can paint a picture without having learned to analyse, synthesise (consciously) or evaluate. However, his behaviour is not ‘original’, it is learned and is born out of memory, therefore he is replicating learned behaviour. The way he holds the brush, the choice of colours and so on, all represent decisions, some more conscious than others, but decisions none the less and therefore show a cognitive process in action.

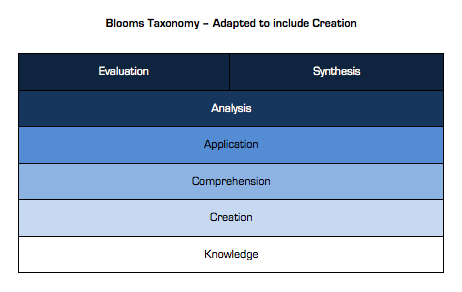

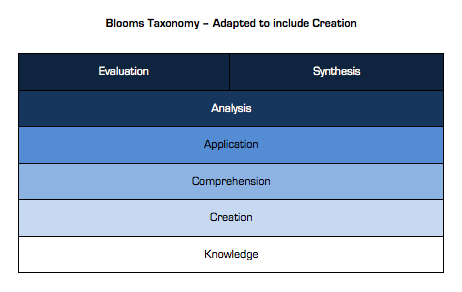

I think that the SOLO Taxonomy that Doug referenced actually comes close to acknowledging ‘creating’ in its more rightful place. In this taxonomy the phrase ‘Do simple procedures’ is used right near the beginning and I would argue that ‘simple procedures’ can be interpreted as ‘creating’. If I were to adapt Bloom’s Taxonomy to incorporate creation, I would suggest something like this.

As you can see I also partly agree with Doug about the placement of Synthesis being wrong although I would see it as equal to evaluation. As cognitive processes the two directly effect each other. Your ability to synthesise something is often based on your judgement but your judgement can be altered as you synthesise something.

My initial involvement in this debate arose after Doug tweeted this:

Rather than this one that started the debate in the first place:

I include this as I think that it reveals a key feature of my thinking in this debate. I don’t believe that Media Literacy is neither ‘passive’ nor is it ‘consumption driven’. To be ‘Media-literate’ you need to have created your own Media.

I have had many conversations in my time with colleagues about the merits and drawbacks of coursework in the Media Studies syllabus. I always come back to this: Can students truly understand the Media if they don’t create it for themselves? They already do in their daily lives but I want them to create texts more critically. I want them to unpack that process of creation. This undoubtedly improves their skills of analysis and their ability to evaluate.

After all, you wouldn’t teach Maths by having students read the sums and then the answers; you make them work through the problems, learning how to solve them for themselves. You wouldn’t teach students to play football by doing nothing more than watching Manchester United on the TV. Without the doing (the ‘creating’) the learning is meaningless.

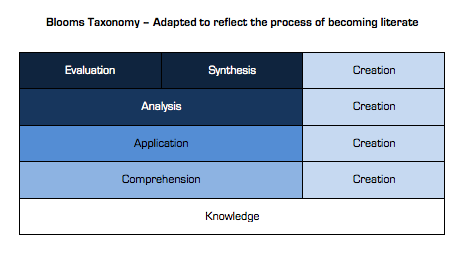

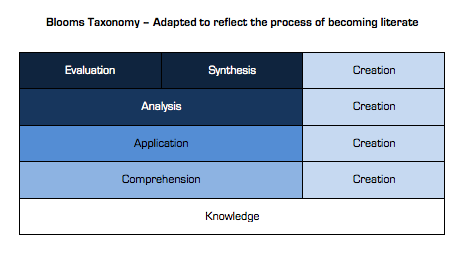

So perhaps Blooms should look more like this with creation featuring alongside every stage of the taxonomy, after knowledge. As ‘creating’ as a cognitive skills is imperative on the path to becoming literate.

My thesis: You can’t be literate if you have never created. To be fully literate you need to create throughout your learning journey, only then will you be able to make meaningful judgements based upon fully informed analysis. Creation can help you piece it all together, what’s more cognitive than that?