This article by Kevin Gannon has been ruminating around my mind since I first read it. Not only do the four lessons that Kevin shares chime with my experiences as an Assistant Principal, but they can be applied by anyone to any situation: work, relationships or life in general.

This article by Kevin Gannon has been ruminating around my mind since I first read it. Not only do the four lessons that Kevin shares chime with my experiences as an Assistant Principal, but they can be applied by anyone to any situation: work, relationships or life in general.

- Not every disagreement is a call to arms.

- How and when I use my voice matters.

- Don’t be afraid to ask for help.

- Be good to people (including yourself).

If one of the above lessons speaks to me the most, it is the third. Whenever I mentor someone new it is the first piece of advice I offer. On the surface, asking for help, seems both obvious and simple. However, when you are placed in a position of authority it can feel far from simple. Asking for help requires the individual to remove their ego from the equation. Fear and/or arrogance are powerful character-traits but they will only hamper long-term success.

Appearing to have all the answers and can help you to demonstrate confidence, which is a much-needed trait in leadership. However, you will ultimately be judged on the success of your projects or areas of responsibility, and if you do not deliver as expected questions will be asked. It is here that cracks will appear and mistakes will be recognised. What often comes out in these situations is that you could have asked for help. Instead, you chose to see such an action as a sign of weakness and were willing to risk the success of the project to massage your ego.

In Gannon’s article, he contextualises this by considering the following common classroom conundrum. Should I admit to my students when I do not know something?

As a teacher, one of the most powerful things I can say to my students is “I don’t know,” because it shows them that I’m still learning, and it usually leads to us saying “let’s find out.” ~ Gannon, 2016.

I have long evangelised the need for educators to free themselves of the title of ‘teacher’ and to be open about their shortcomings. It is folly to present yourself as the fountain of all knowledge, and far more rewarding to experience your students’ learning journey as a collaborator. Learning is ‘interdependent’. It requires constant inquiry and is not nor should not be viewed as a one-way flow of information between educator and learner. When defining ‘connectivism’ in 2007, Stephen Downes stated:

At its heart, connectivism is the thesis that knowledge is distributed across a network of connections, and therefore that learning consists of the ability to construct and traverse those networks.

In very simple terms, learning happens through the connections we make with a number of different individuals across a number of different networks. Combining and connecting these various sources of information enrich our understanding of a topic or idea and free us of the belief that knowledge is derived from one single authorative source.

Within leadership this approach can be applied to the notion of asking for help. Effective administrators and leaders understand that ‘asking for help’ is not a sign of weakness but is rather a sign of strength. Great leaders surround themselves with trusted advisors. Similarly, students writing their Masters or Doctoral theses are encouraged to have a critical friend. We all need a network of people who we can turn to for help; people whose views we trust and value. Even better, people who are prepared to challenge us and ask difficult questions.

Weak leaders surround themselves with yes men who are afraid to argue with them. ~ Knapp, 2012.

Strong leaders do the opposite. They look to those whose views differ from their own in order to fully appreciate the implications that surround a decision that needs to be made, or better define the pros and cons of moving a project forward in a paricular way.

In essence, asking for help is an acknowedgement that before a decision is made or an action is taken, due consideration is required. It is not a weakness. It is a necessary step in ensuring that the decisions you make are well-informed. A decision made in this way is one that you can justify and explain with clarity. Fear and arrogance have no place in such an approach and like the educator who is prepared to say “I don’t know”, an effective leader is prepared to do the same.

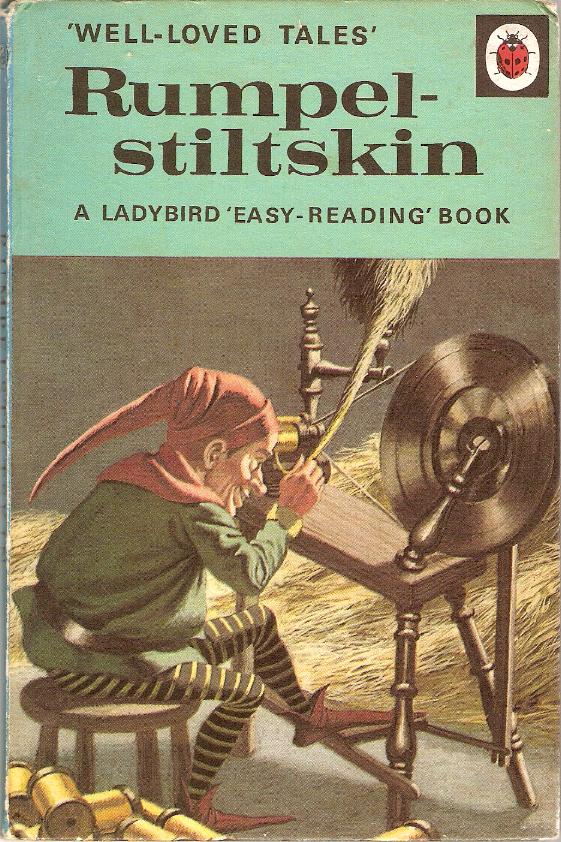

Image via: TOR.COM.

This

This