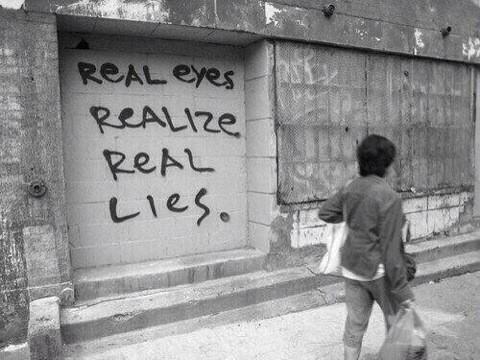

A little truth telling via Banksy, via Doug Belshaw’s weekly newsletter.

Tag: media

MOOC MOOC – Day Four

Before I could join in with Day Four’s activities, I decided that I needed to better understand the concept of ‘Connectivism’.

Connectivism

Stephen Downes states that: “At its heart, connectivism is the thesis that knowledge is distributed across a network of connections, and therefore that learning consists of the ability to construct and traverse those networks.” Which in my mind, could easily be describing my experience in using Twitter to develop a personal learning network (PLN). Through Twitter I have connected with a network of individuals, shared and aggregated resources and ideas, which has resulted in both learning and the (co-)construction of new ideas and resources.

He goes on to outline four process that are integral to connectivism:

- Aggregation

- Remixing

- Repurposing

- Feeding Forward

Considering this list closely, it would appear that connectivism is very similar to constructivism, particularly given that these activities encourage sharing, creation and collaboration.

However, Downes et al., see connectivism as a distinct model of its own. In ‘What is the unique idea in connectivism’, George Siemens explains that “learning is defined as the creation of new connections and patterns as well as the ability to maneuver around existing networks/patterns.” While this sounds very similar to Downes’ interpretation, Siemens emphasis on the “creation of new connections” implies that the learning occurs through networking as opposed to the act of construction. Artefacts created, either individually or collaboratively during MOOCs are, to some degree, a byproduct. The dialogue and connections generated before, during and after their creation is where the learning occurs. The network is the essence of connectivism; the essence of the MOOC.

Siemens continues, asserting that “Coherence. Sensemaking. Meaning. These elements are prominent in constructivism, to a lessor extent cognitivism, and not at all in behaviourism. But in connectivism, we argue that the rapid flow and abundance of information raises these elements to critical importance.” This is certainly true, and within MOOC MOOC this has been more than evident. However, for some participants, the sheer scale of information generated by the network can be overwhelming. Therefore, I would argue that, to be successful in a MOOC, you have to be well-versed in the use of tools that can help you make sense of the information. Moreover, as I have previously written, it is important for participants to be willing to plot their own paths and not feel that they have to read/do everything.

Moreover, connectivism, is a pedagogy that places significant emphasis on interdependence. Perhaps then the most important facet of the MOOC acronym is ‘openness’. Relatively free from geographical, economic, social and cultural constraints, the cMOOC gives rise to democratised, networked-learning that emphasises participation and collaboration.

Participant Pedagogy

Day Four’s task was to consider participant pedagogy. I entered into this having not really had time to look at the reading, but with some strong views about learner participation and the student/teacher paradigm. In my own words

Learning is and should always be in the hands of the learner.

A number of us, decided that some face-to-face interaction was needed and so a Google+ Hanout was instigated. After a few technical problems, Sheila MacNeil, Martin Hawksey, David Kernohan, Alan Ng and I engaged in a fruitful discussion.

The discussion covered a number of related topics:

- the pedagogical models found within the cMOOC/xMOOC dichotomy;

- the position of teacher/lecturer and the way that we (educators) view education/learning;

- the problems with systematised education (sage on the stage, teach to the test culture);

- participant pedagogy, including the problem of the teacher/student paradigm

As I suggest a number of times during the discussion, I believe that the dichotomy of the traditional student/teacher relationship is a false one; based on an out of date system of education. If our goal is to foster a love of learning, then I believe it is necessary for educators to position themselves as learners, facilitators, guides; not as experts. A scary prospect for some.

Pete Rorabaugh argues that:

Critical pedagogy, no matter how we define it, has a central place in the discussion of how learning is changing in the 21st century because critical pedagogy is primarily concerned with an equitable distribution of power… Digital tools offer the opportunity to refocus how power works in the classroom. In its evolution from passive consumption to critical production – from the cult of the expert to a culture of collaboration – the critical and digital classroom emerges as a site of intellectual and moral agency.

This is certainly a thesis that I can support, given that I would describe my own classroom in similar terms. However, I am left asking whether or not such an evolution requires ‘digital tools’ to achieve such equity? Can learning not be democratised within traditional educational settings, without the influence of technology? Does this not, have more to do with shifting beliefs and values about pedagogy and the student/teacher paradigm?

Teo Bishop, makes a similar case, asserting that:

A teacher and a student, when presented as text on the screen, look exactly the same. They are just text. The internet is the Great Equalizer not only because it provides the world with a seemingly unlimited amount of information, but because it reduces us all to font, to pixels, to bits of sound and noise that only begin to approach our full complexity.

Perhaps… although I think this is a naive view. Technology, in this case ‘the internet’, is being given far too much credit. Social status, expertise and power are in no way absent from the world wide web. Blogs and social networks may have given everyone a voice, but that does not mean that everyone is listening.

Technology, itself, does not have the power to improve education. Nor does it have the power to democratise it. The participatory pedagogies alluded to by both Rorabaugh and Bishop require a change in values and beliefs on the part of not just educators, but society as a whole. Moreover, they require a dramatic shift in the priorities of educational institutions. It’s better economics for institutions such as Stanford and MIT to proffer xMOOC style courses, as the investment in participant-based co-creation and the development of networks is labour intensive and difficult to control.

Earlier in the article, Bishop asked what I think is a more important question: “I’m in a position where I can do my best work, and inspire the most dialogue, by openly not having the answers. Do teachers have that luxury?” Yes they do, but they have to be prepared to take risks; to be willing to redefine their role within the classroom. As I shared in the Hangout, I do not consider myself to be a teacher anymore. I am a learner, facilitator, and guide.

On reflection, I wonder to what extent teaching Media Studies has impacted on the way I view education and my role within it. Media Studies is in a continual state of evolution, built on theoretical ideas rather than absolutes; responding to a changing landscape, influenced by social and technological developments. There is always something new to learn, to understand, at no point would I therefore, profess to be an expert.

Jesse Stommel (on Twitter) shared: “Every semester I teach at least one book that I’ve never read before. I read it with the students and actively under-prepare.” Within his words, there is a clue to a deeper philosophy, a belief in shared, interdependent learning between teacher and student. I take a similar approach with my own students, wishing to participate in a ‘learning journey’, where the opinions of student and teacher are of equal value.

Of all of the reading that was provided to support this part of the course, I found Howard Rheingold’s article ‘Toward Peeragogy’ provided the most compelling narrative. Reflecting on the development of what he has coined “peeragogy”, Rheingold draws out, what I believe to be, key tenets in encouraging independent/interdependent learning in any classroom.

In retrospect, I can see the coevolution of my learning journey: my first step was to shift from conventional lecture-discussion-test classroom techniques to lessons that incorporated social media, my second step gave students co-teaching power and responsibility, my third step was to elevate students to the status of co-learner. It began to dawn on me that the next step was to explore ways of instigating completely self-organized, peer-to-peer online learning.

In his classroom, both online and in the lecture hall, Rheingold’s “peeragogy” is built on ‘openness’, ‘social media’, and ‘student voice/choice’ – the same three tenets advocated by Catherine Cronin during a presentation at #EdTech12. Three tenet that can easily be applied to cMOOCs.

The Role of the cMOOC

Returning to one of the articles, from day one of MOOC MOOC, I would argue that Siemens is correct. c“MOOCs are really a platform”, out of which an interdependent network is built. A network that encourages, openness, social connectedness/collaboration, and voice/choice. The cMOOC is nothing without its participants and its participants are in control of the pedagogy.

21st Century Literacy: Two Words

There are no films, TV programmes, advertisements, books, paintings or radio shows. Nor do we watch, observe, gaze, inspect, listen or study. There are only ‘texts’ which we ‘read’.

Sometimes the language we use in the classroom is peripheral, complicating meaning and/or understanding. After all, words such as ‘film’ and ‘advert’ are only generic terms, used to classify texts, in our dumbed down world, where we clamour to have everything fitted neatly into little boxes. Words such as ‘watch’ and ‘gaze’ do nothing more than describe states of being.

None of these terms are helpful in preparing young people to be literate in the 21st century. The values placed on texts such as ‘films’ and ‘TV programmes’, when combined with words such as ‘watch’ or ‘listen’, are predominantly negative. The implication being: ‘no reading is required’. However, any student of Media Studies, Communication Studies or Linguistics will tell you that, this is not true.

Moreover, children are being born into, and are growing up in a “media-saturated society” (Strinati, 1992) where the boundaries between high and low culture have been eroded almost entirely. This is a dangerous world in which young people are growing up. That is, if we don’t begin to treat supposed ‘lowbrow’ texts with the same critical reverence as we have paid to fine works of art, classical music and plays.

It is my contention, that we can take steps towards achieving this, by redefining (and using) just two words. Those words are ‘text’ and ‘reading’.

With my semiotic hat on, I would suggest:

- Text: Any work containing one or more sign.

- Reading: To decode the meaning within a text through the understanding of signs.

If we reduce our classroom language to these two terms and help our students to appreciate the above definitions then we can change the way they look at the world; opening their eyes to the depth of meaning that can be found within a Shakespeare play and Call of Duty. Moreover, we can remove hierarchal precepts and establish a level of equality, in which both (highbrow and lowbrow) texts are read (critically) not watched or played.

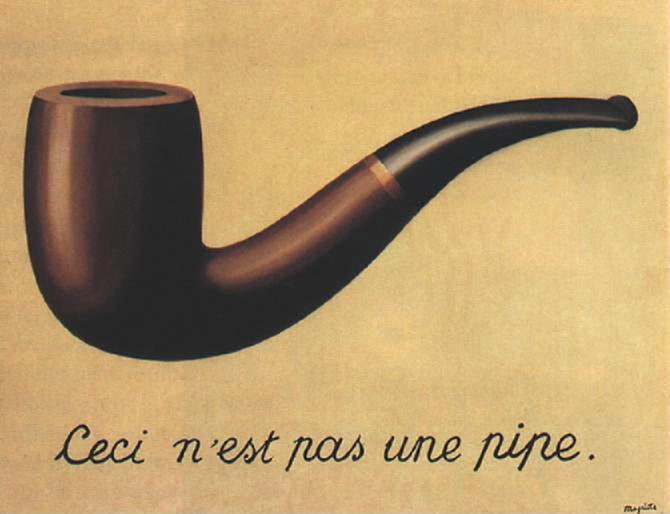

Ceci n’est pas une pipe and the death of Media Studies

Literally moments before I left work on Friday, ready to begin the half-term break, I was sat talking to my friend and colleague Greg Hodgson about literacy. I’ve just put a project together for gifted and talented Year 11 students where they will blog for ten weeks developing their writing skills. The project will encompass in-class and online workshops; seminars; tutorials and support from a professional editor and professional copy-writer. Greg and I discussed the merits of getting all students at our school blogging and how it could impact on improving literacy. What occurred to me during our conversation was that neither of us differentiate between what many refer to as traditional literacy and digital literacy. I don’t like the term digital literacy, never have, as it immediately suggests that understanding digital or media based texts is somehow different to understanding non-digital (analog) texts. The problem is that I don’t believe that. So, here’s an idea: Let’s stop talking about digital literacy and just discuss literacy after all the two are synonymous are they not?

Digital Literacy?

Films, Advertising, Websites, Blogs and Video Games all have narratives and codes that need to be understood; they all offer various meanings and representations ready to be interpreted; and they are all part of a person’s life narrative, so why on should they not be valued in the same way that Literature and Art are valued. And why are we not making sure that our children approach all texts (digital or analog) with an equal level of respect and criticism?

It’s time to ditch the prejudices; it’s time to stop talking about digital literacy as if it is something different to literacy. We shouldn’t spend time debating what digital literacy is, we should be asking why teach literacy at all? Teaching literacy is not only about getting kids to read books, it’s about teaching our children to read signs, to decipher meaning out of symbols. When those symbols and signs are communicated by road signs we value their purpose encouraging them to get driving lessons and pass their driving test. When those symbols and signs are communicated through a YouTube video or a Video Game we do not seem to value them at all. Surely, if our children are going to be able to survive in this ‘uncertain future’ that lies before them they need to be literate. And not just literate in that they can read words but that they can decipher all texts placed in front of them, analog or digital. The age of the social network, of online collaboration, of information at your finger tips is not some distant notion, it is the state in which we live now and future generations are being born into. The army is using Video Game technology to train its soldiers. Why are we all not using this technology to help prepare our children for their futures? We have a responsibility to make sure that they are literate; with the skills to understand the messages and values that are sewn up in the plethora of texts that they consume on a daily basis.

Ceci n’est pas une pipe.

We only have to look to René Magritte’s painting ‘The Treachery of Images‘ [1928-29] to see that this argument has existed for 40 years, before video games grabbed our attention and 60 years before Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web. Magritte illustrates the duality that all texts, whether made up of words or images, pose for us. In his painting Magritte is commenting on the process of signification; the basis of communication in that all images have more than a single layer of meaning by their very nature; that all texts offer representations and therefore are open to interpretation. This (IMO) is the fundamental reason that literacy should be at the heart of any school curriculum and is the basis for my belief that separating literacies into “analog” and “digital” is actually a banality that should be avoided. It does not matter what the text is, what matters is that we have the skills to be able to understand it.

Understanding the mirror

We can look to more recent theorists to see that the purpose and need for literacy is only increasing. As our world has become more and more saturated by modern media, only expedited by the rapid development of the World Wide Web, theorists have been warning of a need to be more literate no matter what form the text takes.

Dominic Strinati in ‘An Introduction to the theories of popular culture‘ [1995], states: “The mass media…were once thought of as holding up a mirror to, and thereby reflecting, a wider social reality. Now that reality is only definable in terms of surface reflection of the mirror.” Strinati is suggesting that the way in which we understand our world is through the media that we consume. This raises an important consideration, particularly for teachers. If as Strinati suggests that reality is born out of the mirror then we surely have a responsibility to help our students understand the mirror, whether it’s a magazine article, TV news segment or web page.

Jean Baudrillard, ten years earlier, in is his book ‘Simulacra and Simulation‘ [1985], sets out an even deeper fundamental reason that we should teach young people to be critical and question their perceived reality. Baudrillard suggests that modern culture/society is made up from both simulations (copies of real places and things) that become real through perception and simulacra (copies without an original).

For example, the film Jurassic Park, presents through CGI and animatronics a highly convincing simulation of dinosaurs which we as the audience accept even though we have never seen a real live dinosaur. We accept the copy (simulacra) as reality although there is no original for it to have been copied from.

If simulated Media form our reality then we must ensure that young people are equipped to recognise this and question the texts from which they are forming their understanding. What if dinosaurs bore no resemblance to their CGI counterparts? For many the film will have become a key source in their understanding of the dinosaur, yet it is a lie, a false creation, a guess?

Is it acceptable to allow prejudice to continue? Literature and Art are valued and therefore worthy of study and criticism. Should films and websites not be valued in the same way and come under the same level of scrutiny?

The death of Media Studies?

The problem is that we often accept the notion that there is a difference between literacy and digital literacy. Perhaps the development of Media Studies as a discreet subject is partly to blame for this? Much of the discussion about digital literacy is confused with concepts such as ‘media literacy’. The problem here being that there seems to be a deeply held belief that being “media literate” means being able to create and edit video, be eSafe and use a computer effectively (isn’t that ICT?). This need to categorise literacy, chunking it, ignores the messages that Magritte, Baudrillard and Strinati have been trying to draw our attention to. Being literate is about reading, about perception, about being critical. These skills are necessary in any and all subjects

What’s more, all forms of media require us to read, perceive and be critical and we can encounter them at any time and within any subject. Just as it should not fall to ‘English teachers’ to be the soul authority when it comes to reading Shakespeare and writing stories why should it be that ‘Media Studies teachers’ are expected to be the soul authorities when it comes to understanding Films, Video Games and the World Wide Web? If the answer to this means the death of Media Studies as a distinct subject then so be it as the study of “the Media” ought not be separate from the study of Literature, Science, History, Religion or Philosophy, as the texts that make up a Media Studies curriculum all have a place in any and all of the other subjects found within the school curriculum.

A 21st century definition of Literate

Media literacy, eLiteracy, digital literacy are terms that I believe do nothing more than cause confusion. There should be only literacy. Plain and simple. Most dictionaries state that to be ‘literate’ is to be able to “read and write“. I think that this is out dated, I believe that a more fitting definition is as follows:

Literate: to have the ability to understand, criticise, and (re)create any text, analog or digital.

Welcome to ‘the zone of optimal challenge’

Last week Merlin John (@merlinjohn) published an article (through FutureLab) titled: “Welcome to ‘the zone of optimal challenge’.” The article is about the Online Games Design course that I was involved with and have tweeted about often using the hash tag #cmdgames. Merlin asked me to provide a quote for the article and I was more than happy to oblige.

He followed up the FutureLAb article with an additional piece on his own blog: Merlin John Online titled: “Chalfonts scores high with Games Design Workshop”.

You can find out more about both the Online Games Design course and the Creative Media Diploma on the Chalfonts Community College ‘Creative Media Diploma Blog’‘. Working to a “real”, “creative” brief, the students collaborated in groups to produce a game related to the 2010 paralympics. The finished work is fabulous and links to play the games can be found here.

The online course was a tremendous success, breaking new ground for online learning and providing further proof of the value that video based conferencing tools (Adobe Connect) can have within education.

The brainchild of Greg Hodgson (@greghodgson) and Roxana Hadad (@rhadad), the online course lasted for 10 weeks and was supported by classroom teaching and a dedicated Moodle course – used to help the students remain organised as they worked on developing their skills as both game designers and game makers.

The students thoroughly enjoyed taking part and the level of progress they made was fantastic. Alongside Greg and Roxana there were a wide variety of people involved in making the course happen including myself, Hannah Stower (@hstower) – Leader for the Creative Media Diploma, Ian Usher (@iusher) – Buckinghamshire E-Learning Co-ordinator, and a sleugh of games designers (who spoke on the course) including Colin Maxwell (@camaxwell) and Josh Diaz (@dizzyjosh).

Thanks to Merlin for writing the articles. I really enjoyed being involved in delivering the course and look forward to helping to improve and deliver it next year.

If you would like to know more about the online course or about our use of Adobe Connect please contact me by email or send me a tweet @jamesmichie.