Literally moments before I left work on Friday, ready to begin the half-term break, I was sat talking to my friend and colleague Greg Hodgson about literacy. I’ve just put a project together for gifted and talented Year 11 students where they will blog for ten weeks developing their writing skills. The project will encompass in-class and online workshops; seminars; tutorials and support from a professional editor and professional copy-writer. Greg and I discussed the merits of getting all students at our school blogging and how it could impact on improving literacy. What occurred to me during our conversation was that neither of us differentiate between what many refer to as traditional literacy and digital literacy. I don’t like the term digital literacy, never have, as it immediately suggests that understanding digital or media based texts is somehow different to understanding non-digital (analog) texts. The problem is that I don’t believe that. So, here’s an idea: Let’s stop talking about digital literacy and just discuss literacy after all the two are synonymous are they not?

Digital Literacy?

Films, Advertising, Websites, Blogs and Video Games all have narratives and codes that need to be understood; they all offer various meanings and representations ready to be interpreted; and they are all part of a person’s life narrative, so why on should they not be valued in the same way that Literature and Art are valued. And why are we not making sure that our children approach all texts (digital or analog) with an equal level of respect and criticism?

It’s time to ditch the prejudices; it’s time to stop talking about digital literacy as if it is something different to literacy. We shouldn’t spend time debating what digital literacy is, we should be asking why teach literacy at all? Teaching literacy is not only about getting kids to read books, it’s about teaching our children to read signs, to decipher meaning out of symbols. When those symbols and signs are communicated by road signs we value their purpose encouraging them to get driving lessons and pass their driving test. When those symbols and signs are communicated through a YouTube video or a Video Game we do not seem to value them at all. Surely, if our children are going to be able to survive in this ‘uncertain future’ that lies before them they need to be literate. And not just literate in that they can read words but that they can decipher all texts placed in front of them, analog or digital. The age of the social network, of online collaboration, of information at your finger tips is not some distant notion, it is the state in which we live now and future generations are being born into. The army is using Video Game technology to train its soldiers. Why are we all not using this technology to help prepare our children for their futures? We have a responsibility to make sure that they are literate; with the skills to understand the messages and values that are sewn up in the plethora of texts that they consume on a daily basis.

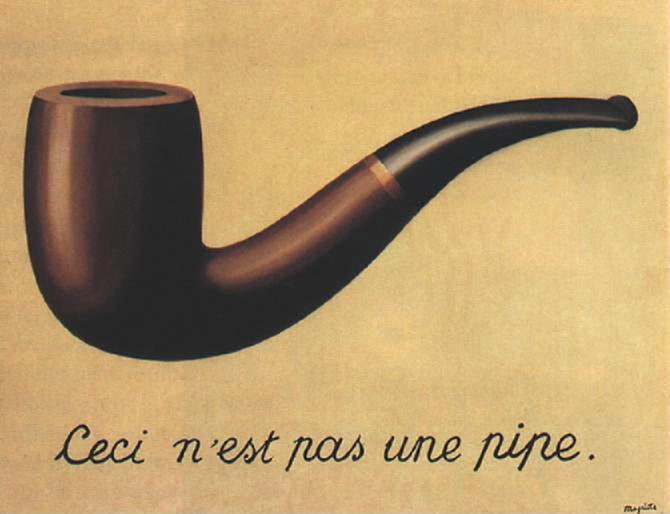

Ceci n’est pas une pipe.

We only have to look to René Magritte’s painting ‘The Treachery of Images‘ [1928-29] to see that this argument has existed for 40 years, before video games grabbed our attention and 60 years before Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web. Magritte illustrates the duality that all texts, whether made up of words or images, pose for us. In his painting Magritte is commenting on the process of signification; the basis of communication in that all images have more than a single layer of meaning by their very nature; that all texts offer representations and therefore are open to interpretation. This (IMO) is the fundamental reason that literacy should be at the heart of any school curriculum and is the basis for my belief that separating literacies into “analog” and “digital” is actually a banality that should be avoided. It does not matter what the text is, what matters is that we have the skills to be able to understand it.

Understanding the mirror

We can look to more recent theorists to see that the purpose and need for literacy is only increasing. As our world has become more and more saturated by modern media, only expedited by the rapid development of the World Wide Web, theorists have been warning of a need to be more literate no matter what form the text takes.

Dominic Strinati in ‘An Introduction to the theories of popular culture‘ [1995], states: “The mass media…were once thought of as holding up a mirror to, and thereby reflecting, a wider social reality. Now that reality is only definable in terms of surface reflection of the mirror.” Strinati is suggesting that the way in which we understand our world is through the media that we consume. This raises an important consideration, particularly for teachers. If as Strinati suggests that reality is born out of the mirror then we surely have a responsibility to help our students understand the mirror, whether it’s a magazine article, TV news segment or web page.

Jean Baudrillard, ten years earlier, in is his book ‘Simulacra and Simulation‘ [1985], sets out an even deeper fundamental reason that we should teach young people to be critical and question their perceived reality. Baudrillard suggests that modern culture/society is made up from both simulations (copies of real places and things) that become real through perception and simulacra (copies without an original).

For example, the film Jurassic Park, presents through CGI and animatronics a highly convincing simulation of dinosaurs which we as the audience accept even though we have never seen a real live dinosaur. We accept the copy (simulacra) as reality although there is no original for it to have been copied from.

If simulated Media form our reality then we must ensure that young people are equipped to recognise this and question the texts from which they are forming their understanding. What if dinosaurs bore no resemblance to their CGI counterparts? For many the film will have become a key source in their understanding of the dinosaur, yet it is a lie, a false creation, a guess?

Is it acceptable to allow prejudice to continue? Literature and Art are valued and therefore worthy of study and criticism. Should films and websites not be valued in the same way and come under the same level of scrutiny?

The death of Media Studies?

The problem is that we often accept the notion that there is a difference between literacy and digital literacy. Perhaps the development of Media Studies as a discreet subject is partly to blame for this? Much of the discussion about digital literacy is confused with concepts such as ‘media literacy’. The problem here being that there seems to be a deeply held belief that being “media literate” means being able to create and edit video, be eSafe and use a computer effectively (isn’t that ICT?). This need to categorise literacy, chunking it, ignores the messages that Magritte, Baudrillard and Strinati have been trying to draw our attention to. Being literate is about reading, about perception, about being critical. These skills are necessary in any and all subjects

What’s more, all forms of media require us to read, perceive and be critical and we can encounter them at any time and within any subject. Just as it should not fall to ‘English teachers’ to be the soul authority when it comes to reading Shakespeare and writing stories why should it be that ‘Media Studies teachers’ are expected to be the soul authorities when it comes to understanding Films, Video Games and the World Wide Web? If the answer to this means the death of Media Studies as a distinct subject then so be it as the study of “the Media” ought not be separate from the study of Literature, Science, History, Religion or Philosophy, as the texts that make up a Media Studies curriculum all have a place in any and all of the other subjects found within the school curriculum.

A 21st century definition of Literate

Media literacy, eLiteracy, digital literacy are terms that I believe do nothing more than cause confusion. There should be only literacy. Plain and simple. Most dictionaries state that to be ‘literate’ is to be able to “read and write“. I think that this is out dated, I believe that a more fitting definition is as follows:

Literate: to have the ability to understand, criticise, and (re)create any text, analog or digital.