This post expands on ideas I shared, in a series of tweets, with John Finlayson (@MrFinobi) about ‘learning objectives’.

Learning objectives can be a powerful tool in a teacher’s toolkit. At the same time they can be a teacher’s Achilles heel, either tied in with a rigid lesson structure that has been forced upon them or (as I see too often) misunderstood for being a statement of what is going to be produced rather than what is going to be learned.

Learning objectives are integral to assessment for learning

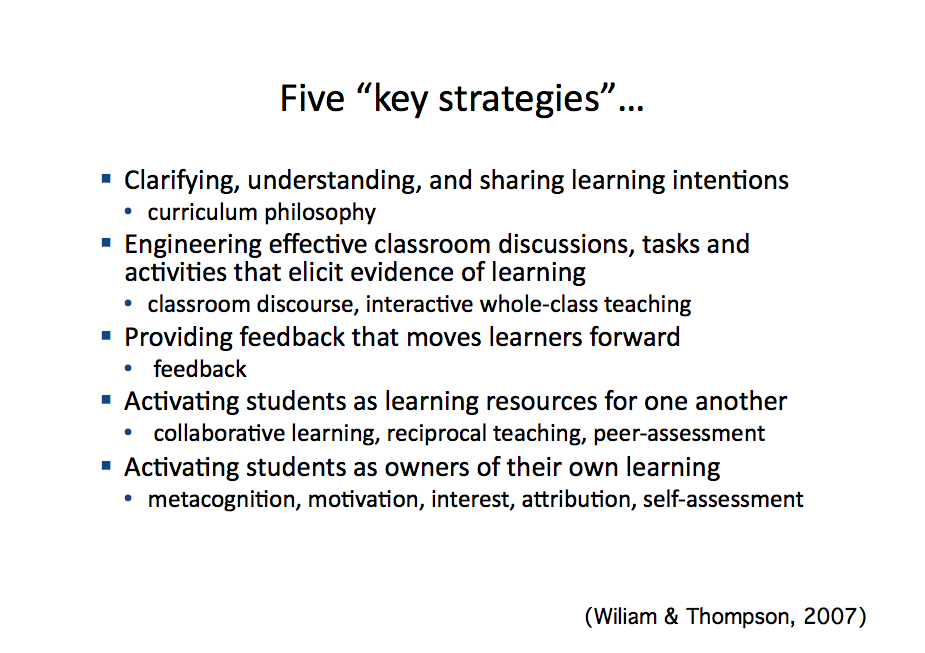

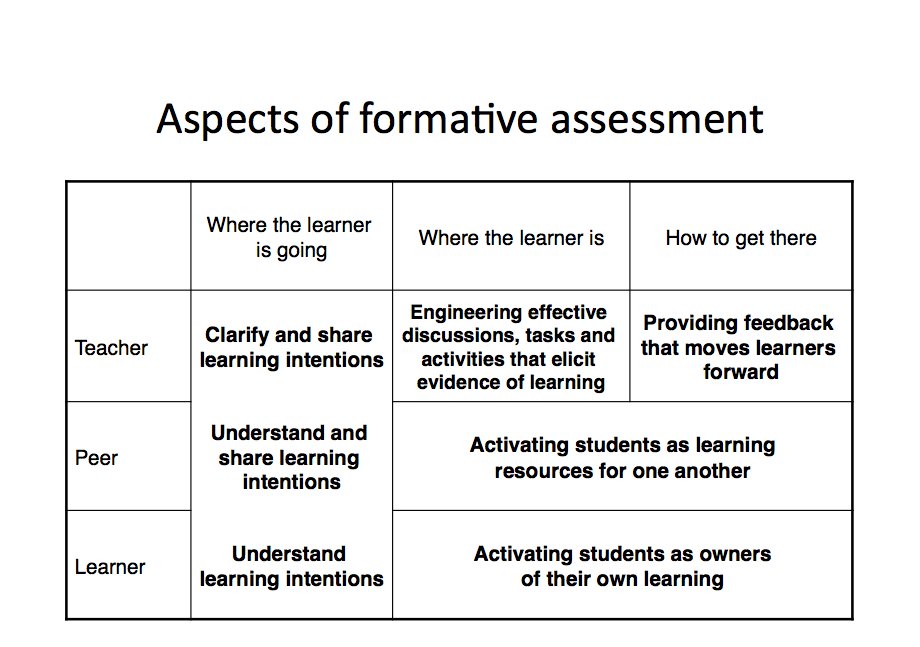

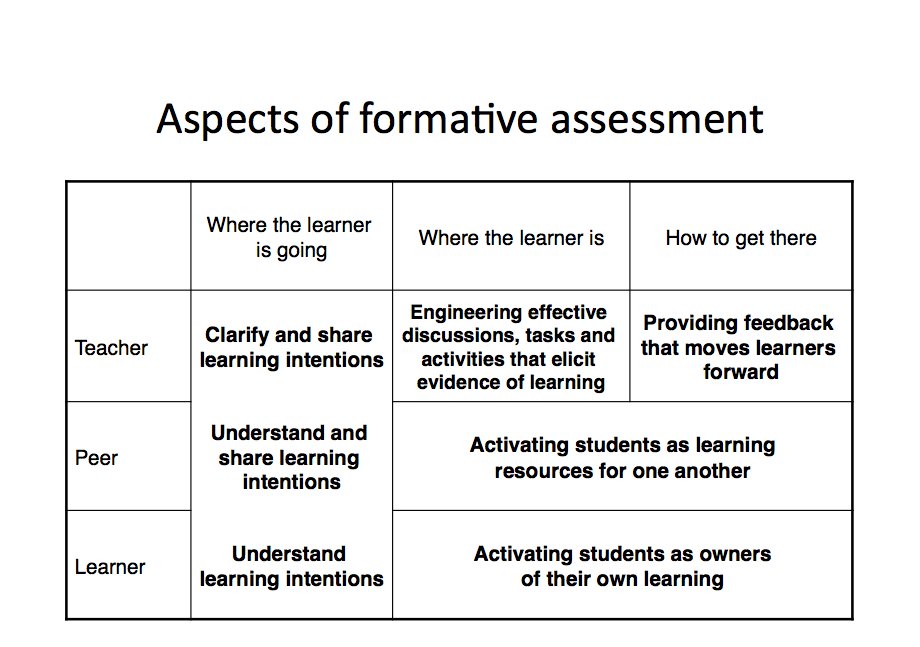

If used correctly, learning objectives can be one of the keys in developing an effective assessment for learning strategy. Dylan Wiliam (considered an expert inAfL) regularly refers back to the following two slides:

His contention is that learning objectives are an integral part of effective AfL strategy. He argues that sharing of learning objectives opens up a discourse about learning. (Wiliam, 2010) I am inclined to agree and would recommend that all teachers experiment with the way they share learning objectives.

One of the most effective ways to ensure that you are using learning objectives effectively with your students is to consider the work of Shirley Clarke.

Taught Specifics

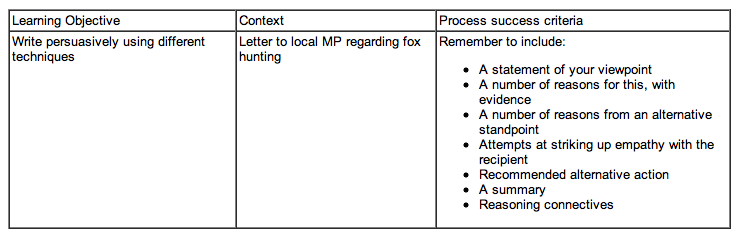

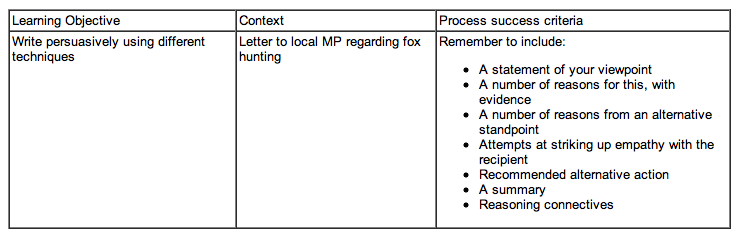

In her book ‘Formative Assessment in the Secondary Classroom’, Clarke explores the value of learning objectives in significant detail. She discusses the ‘taught specifics’ inherent within learning objectives arguing that teachers need to “move away from “PRODUCT” oriented success criteria to “PROCESS” oriented success criteria” (2005, 30-31).

She goes on to argue that if used correctly, process success criteria can set the agenda for the learning and also provide a specific focus for peer and self-assessment activities. Having built Clarke’s approach into my lessons for some time now, I have seen significant improvement in the way my students approach their learning – confident in discussing what they are learning, why they are learning it, and how they will succeed in doing so.

Clarke also suggests that students should write learning objectives down. This I disagree with. I do not feel it is necessary for students to write down the learning objectives during every lesson. Nor, do I believe that a teacher needs to put the learning objectives on the board during every lesson.

Depending on what is to be learned I take a variety of approaches to introducing the learning objectives. Sometimes, I put the success criteria on the board and then ask students to discuss what they think the learning objective is going to be. Other times, I only put the learning objective on the board and ask the students to decide on what the success criteria will be. This is an important step in developing the discourse about learning that Wiliam refers to.

Discovery

David Didau (@LearningSpy) in a recent blog post discussed the value of ‘discovery learning’, where the teacher does not begin with an objective or question but creates a sense of engagement and curiosity through modelling and student interaction.

So how about trying this? Stride purposefully into the room and, without a word, begin drawing a face on the board. Draw an arrow next to the head and write, “Head like an egg”. Turn to the class to see the reaction. Offer them the pen. Don’t worry if they don’t get it yet, continue by labelling the eye with, “Eye like a crater”. Sooner or later they will begin to join in and end up sputtering with delighted laughter at all the hilarious comparisons they make.

How much better is this than waltzing in with the question, “So, can anyone tell me what a simile is?” Anyone inclined to dismiss discovery learning as nonsense need look no further. The power of students discovering for themselves the point of a simile (or apostrophe, or subordinate clause or whatever) is much more likely to be memorable than their teacher just telling them.

This same approach can be applied to learning objectives. Like many good teachers I do not only spend time discussing where the learning is going but also build in time to reflect on the learning. It can be, again depending on the context, to not reveal the learning objective until the end of the lesson. Allow the students to muddle their way through – it can often be quite liberating and lead to unexpected learning outcomes alongside the ones you intended.

An Incremental View

John’s original tweet asked me if I ‘differentiated’ learning objectives. My response was an unequivocal ‘No’. The reason for this is because I subscribe to an ‘incremental view’ rather than a ‘entity view’ of intelligence and learning (Dweck, 1999). A student’s learning potential is not pre-determined. Both the least and most able students in my classroom have the potential to progress and they need to learn to utilise the same skills in order to pass their exams. As such I feel it is wrong to differentiate objectives by skill or outcome.

The box provided (on my school’s lesson planning sheet) for entering learning objectives is broken down into the following sections: ‘All, Most, Some’. I know this has been set out this way as it is something that Ofsted like to see. However, I am not convinced by it, having never seen the research behind it. I have seen lesson plans dutifully filled in, explaining how different sets of students will learn different skills.

All students will be able to describe…

Most students will be able to analyse…

Some students will be able to evaluate…

Last time I checked, every single one of my students was capable of learning to do all of those skills, if taught the right way. Last time I checked some students found evaluating easier than analysing. Whichever taxonomy you prescribe to (Bloom’s / SOLO), the skills listed do not exist within a hierarchy or on a continuum. They are not linear. Learning is messy. Based on my experiences over the last nine years, learners will acquire different skills at varying rates in varying orders of preference, based on a diverse range of factors.

None of this is to say that I don’t believe in differentiation. I do. In my mind, differentiation is not about learning objectives or outcomes, it is about teaching and learning. Differentiation takes place during the lesson. It is present in the way I formulate groups for discussion and projects. It is present in who I choose to spend my time with during a lesson and what I do with them. It is in how I deploy my learning assistant. It is about focussed differentiation; targeted support; the development of independent learning skills.

The Map

I believe that in a classroom learning objectives should be shared; every student working towards similar goals but in different ways and at different speeds. The learning objectives set the direction of the learning. How the map (success criteria) is formulated however is sometimes up to me and sometimes up to them. Sometimes, we lose the map and get lost along the way. Together, through communication and sharing, we find our way back. And, sometimes there is no map; we get lost on purpose, excited to see where we might end up.

References:

- Clarke, S. (2005) Formative Assessment in the Secondary Classroom, London: Hodder Murray.

- Dweck, C. S. (1999) Self-Theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development, Philadelphia, PA: The Psychology Press.

- Wiliam, D. (2010) Innovation that works. Workshop at SSAT conference, Birmingham, Novemner. Retrieved 28 November 2010 from the World Wide Web: http://web.me.com/dylanwiliam/Dylan_Wiliams_website/Presentations.html