Having turned 30 this past December I often find myself thinking about my brain, impressed by the fact that it keeps working; consuming more information all of the time. This in turn gets me to thinking about my students brains and what my role is in helping to fill them, which brings me to the purpose of this post. Once a week I am going to focus on a quote from literature to help illustrate a point or idea.

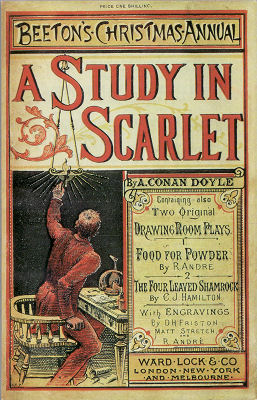

For the 1st of these posts I wish to direct you to chapter 2 from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes novel: A Study in Scarlet. Watson is amazed by both Holmes’ knowledge and his ignorance after discovering that he was unaware of the fact that the Earth rotates around the Sun. Holmes explains his apparent shortcomings quite wonderfully.

“You appear to be astonished,” he said, smiling at my expression of surprise. “Now that I do know it I shall do my best to forget it.”

“To forget it!”

“You see,” he explained, “I consider that a man’s brain originally is like a little empty attic, and you have to stock it with such furniture as you choose. A fool takes in all the lumber of every sort that he comes across, so that the knowledge which might be useful to him gets crowded out, or at best is jumbled up with a lot of other things so that he has a difficulty in laying his hands upon it. Now the skilful workman is very careful indeed as to what he takes into his brain-attic. He will have nothing but the tools which may help him in doing his work, but of these he has a large assortment, and all in the most perfect order. It is a mistake to think that that little room has elastic walls and can distend to any extent. Depend upon it there comes a time when for every addition of knowledge you forget something that you knew before. It is of the highest importance, therefore, not to have useless facts elbowing out the useful ones.”

“But the Solar System!” I protested.

“What the deuce is it to me?” he interrupted impatiently; “you say that we go round the sun. If we went round the moon it would not make a pennyworth of difference to me or to my work.”

It is at this point that I turn to the title of my post. It is clear that if Holmes were alive and kicking in the 21st Century he would be very pleased with the current system of British education – specifically the ‘narrowing’ or ‘specialising’ process (depending on how you view it) that takes place at 14, 16 and 18 years of age. By the time a young person leaves university they will have surely emptied their “brain-attic” of any and all “useless facts”, keeping only the “useful ones” in pursuit of their chosen career.

However, I believe that both the great Sherlock Holmes and the current system of education in Britain are wrong. Holmes’ usually exquisite reasoning has failed him. In the 21st century it is unlikely that any person leaving education will have an exact understanding of what their future career may be. Jobs change frequently and new ones are invented all of the time in a world that never stops moving, never stops adapting and evolving. It is therefore, impossible to say that any one piece of information is “useless”. What may seem like a trivial nugget of knowledge may one day be a vital component of someone’s “brain-attic” helping them to complete a task or to forge ahead with their chosen career.

While I appreciate that some of you will disagree with me, I for one, am tired of hearing the following question come from a 15 year-old’s mouth: “What do I need to know this for? I don’t see why I need to be able to read Shakespeare in order to cut someone’s hair!” For me this exemplifies the flaws in Holmes’ thinking. While being able to read Shakespeare may not help the 15 year-old to cut hair after they leave school at 16 it will have taught them something about British heritage; it may help them two years later should they become dissatisfied with their chosen career and decide to go to college; and it might certainly be useful to them when they have their own 15 year-old who is reading Romeo & Juliet for the first time and they are asking mum or dad to sit down and read it with them.

Holmes may not be completely wrong though. There probably is some knowledge that will be useless to us no matter what but even the most benign facts such as the name of Katie Price’s current husband will be useful to someone: a journalist at the Sun newspaper perhaps, a celebrity blogger or a university professor who teaches their students Media Studies or Social Studies.

The fact of the mater is this: No information is “useless”! The current system of education in Britain is telling young people that some information is more important than others, that some subjects are more valuable than others and that it is okay to ignore information, ideas and thoughts if they don’t bare some direct relationship to the subjects they are taking or the career path they have decided to follow. This for me like Holmes’ explanation if his own ignorance is very problematic.

I personally feel let down by my own education – I was not fully prepared for the rigours of the working world and like so many learned just as much working as a part-time supervisor at Superdrug as I did studying for my degree. I learned to use Maths properly on the job – having been allowed to give it up at sixteen. My wife, an Arts History Major from the College of Charleston, SC, USA was still taking ‘Math’ classes while obtaining her degree – the application of number being actually quite important to the day to day running of a gallery or museum. On the job I also learned to use Excel with real purpose rather than the laughable task used by many ICT teachers today – to plan a party on an Excel spreadsheet – who does that I ask you? Who plans their parties using Excel? I don’t – a paper and pen usually suffices!

If I had been made to continue with a broader range of courses I have no doubt that I still would have made it to University but I may have had greater choice about what I wanted to do. I may have retained more of that useful Maths that I struggled through at GCSE but only saw the true value of when as a University student I was promoted from Shop Assistant to Supervisor – a position that meant I had to balance the tills at the end of the day, squaring away the days takings. It was worth it for the pay rise that came with it but would have been easier if I had not been allowed (encouraged in fact) to let that “useless” Maths (like long division and percentages) be elbowed out of my “brain-attic”.

I am grateful to my time working in retail – it meant that I had the expertise to pass my QTS Skills test in Numeracy during my PGCE. In fact as an English PGCE student this and the ICT test were the exams I feared the least. I was more worried that my spelling or grammar would let me down on the Literacy test. This ill feeling mainly being the product of not wanting to embarrass myself more than anything else.

The word count reads 1279 so I had better come to some sort of a conclusion! A child’s brain is like an empty “attic” and it i my job to help fill it but not simply with Shakespeare, Browning and Miller; not simply to be able to analyse a quotation or dissect a scene from EastEnders but to teach them to question the status quo; to conduct primary and secondary research effectively; to understand the links between social media, geography, politics and class amongst many other connections that can be made between subjects, ideas and thoughts. My students’ “brain-attics” have walls but they are pliable, expandable, not set by stone and mortar. They are open to using technology to aid their learning but also to know when to put it down. They appreciate, because I will them to, that Art is as valuable as English and History is as valuable as Maths. And you know what their is enough room in their “brain-attics” to take it all in!

My concern is this! What happens to my Year 10 students in 18 months time and they become A-Level students or they leave school. Will their “brain-attics” keep being filled up? Will they keep expanding their minds thirsting for knowledge or will they start to haemorrhage apparently “useless” information that they believe they don’t need any more because they “don’t do English no more, didn’t see the point of Shakespeare any way!”

Sherlock Holmes – your reasoning is simply wrong! While you don’t see why knowing that the Earth rotates around the Sun will help you right now you are ignorant of the fact that it might be helpful to you at a later date. This is the problem and challenge that our young students face today being the recipients of “a very British Education.”

You're right – this kind of thinking is a huge problem, and pupils' (and teachers'!) attitude to numeracy is a particular concern. To me, it seems crucial to encourage pupils to see skills learnt in school as a huge toolset rather than training for a specific career.

And as for Holmes, I've always loved that quote of his. I wonder how well his methods would translate to the 21st century?

Holmes' knowledge is not at all narrow and encompasses massive amounts of information of no use to the rest of us. What "pennysworth of difference" does it make to your work to know what Holmes knows about the look different cigar ashes or reliable street urchins? Surely you would scoff if I suggested it were important for you to learn it because such knowledge might possibly be important to you at some future date.

If cigar ash is not important to you, why should the solar system be important to Holmes?

All of us acquire knowledge that is important because of our particular areas of interest. Some children have an interest in passing through school successfully, so they acquire the knowledge we teach them. Others, like Holmes, dismiss much of that knowledge as not pertinent to their interests as soon as the exam is over.

While school should expose students to various fields of knowledge, various points of view, and people from different backgrounds, whether or not a particular bit of information is, or might be useful, is the decision of the individual.

If I have no interest in what you are trying to teach me I will not retain it. Thinking that you, or the educational system, can be the the arbiter of what any particular student need know is a massive conceit.

Students asking you why they will ever need or when they might use the information in your lessons are trying, in their immature, inarticulate way, to tell you that your lessons are not compelling, not pertinent to their interests, and that you have not helped them connect what you are trying to teach to something they already know.

It is all well and good to criticize the education system — and if yours is anything like the one in which I teach it provides unending opportunities — but the place to start looking for the ways to expose students to more knowledge and enhance their engagement with it is in one's own practice.

You are quite right – perhaps what I am exhorting is the need for a change in attitude from the wider British society.

As for Holmes – I think his methods would serve him well. I do him a disservice really but the quote spoke to me and was a good starting point for this particular blog post.

I agree Holmes' knowledge is not at all narrow, you are right. I was simply using the quote as a starting point to address what I feel is a relevant issue.

As for my teaching practice, well, it is very good and it is rare that I hear "what is this for or why do I have to learn this" but I know that it is there in the back of (some of) their minds.

However, no matter how much you do, how much time and effort you put in as an educator you can not get to them all. With classes of 30-34 students it is extremely difficult. Added to which, I am usually given the more difficult classes. I strive every day to make what I teach relevant and real for them.

I went to school each morning, eager to be there. I could not wait until the bell went so that I could find out what I was going to be learning about that day. But this for me has changed in the UK quite significantly and while I would be naive to believe that there was ever a time when all young people felt the way I did about school, there were more then than there are now.

Knowledge is power and the young do not always know what they should learn or need to know. They are, after all, "immature". Learning needs to be meaningful, it needs to have purpose and it needs to be well thought out. But it does not always need to be fun. I am a teacher not an entertainer. I will make my lessons engaging, reflective, about more than just knowledge, skills based and I will make them relevant. But that does not mean that they will always be fun. That does not mean that everything I teach will be pertinent to the interests of every person in the room.

Sometimes knowledge is there for its own sake. What is wrong with bettering yourself through the pursuit of knowledge. I did not go to university to get a job, I went to university to become a wiser person.

What I was trying to say in my blog post is that I could have arrived at university better prepared, had I not been forced to narrow down to 3 subjects at 16 years of age as the British education system requires you to do. While in my classroom I teach far more that Media and English but my students could use some help. If they were able to continue with a broader range of subjects up to the age of 18 they would be better prepared for both university and the world of work.

No, learning is not and should not necessarily be fun in the sense of being a clown and entertaining students.

I also teach what others think of as difficult students. Mine respond to challenges they have a chance of succeeding at. Success leads to a bigger challenge, but also one they have a chance of succeeding at.

I agree that students should not be forced to narrow to three subjects at age 16, but I also think the whole idea of subjects needs to be re-examined.

Teaching holistically and showing how all learning is interconnected is a better path to students desiring wide areas of knowledge and experience.

Yes, that leaves me open to the question of whether I prefer broad, shallow learning or deep, narrow learning. I favor both; deep learning of skills and fields of student interest, broad learning through following the interconnections inherent in those fields.

I agree with you – the subjects as we teach today need to be re-examined. For example the skill base within English and Media Studies are exceptionally similar and without a doubt intrinsically linked.

However, they are deemed to be separate subjects and are valued very differently by students, teachers, parents and the media themselves. One is not necessarily more relevant than the other but the kids I teach spend more time online and on their iPods than they do reading books.

As to learning I believe that broad learning can be deep. Perhaps it is here though, that we are both touching on a larger social issue, in that we both teach in countries where education is taken for granted rather than seen as something of value.

If our students did not have access to education like many people in third world countries don't, they would be prepared to study as many subjects as possible for as long as possible, as they would see it as a great gift. This would lead to "deep broad learning", would it not?

Ultimately, you are right and the majority of my teaching, like yours, is now skills based. They need the tools more than the knowledge. This is perhaps the result of the onslaught of technology to which I am not going to bemoan as I am a full embracer of technology inside and outside of education. "I tweet therefore I am"!